Balancing technology, human connection + upgrading basic protection

By: Kyle Kirkpatrick

Construction superintendents face a daily challenge: maintaining safety across complex jobsites with multiple trades, varying skill levels and tight schedules. The most effective safety programs combine technological innovation with human-centered leadership practices — a balanced approach that creates safer work environments while improving productivity.

Automation that protects workers

On large construction sites, workers perform physically demanding tasks that require careful attention to proper techniques and safety protocols to prevent potential injuries. While tools and technology can reduce risk, workers and their supervisors must keep safety at the forefront.

Take utility-scale solar projects as an example: workers carry photovoltaic panels weighing 80-100 pounds across uneven terrain, then lift them onto racks about shoulder high — a repetitive, strenuous task that can cause strains and injuries.

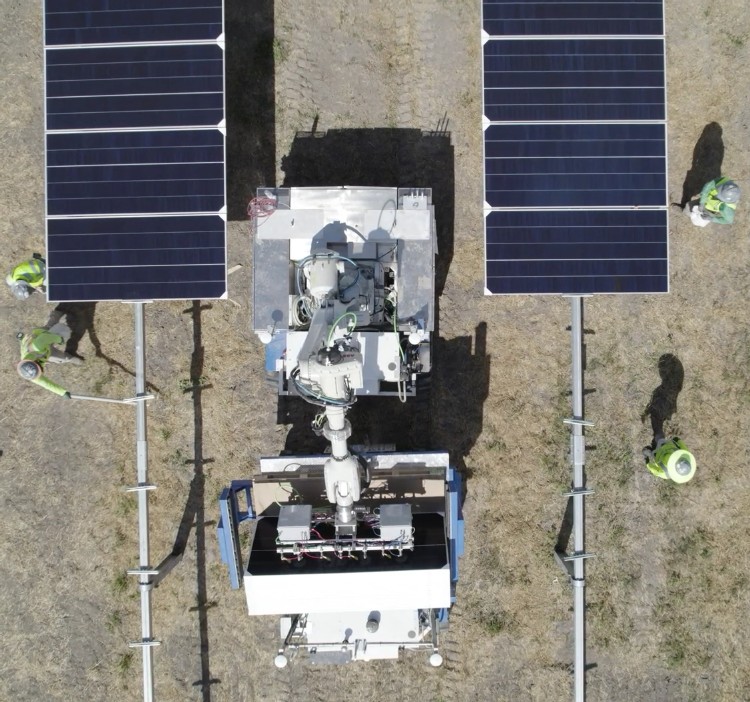

Innovative automation solutions are changing this dynamic. Advanced robotic systems are being developed to handle the heaviest lifting, while skilled workers focus on precise connections and quality control. Solar building robots, like the one Rosendin created, take years to develop and test, but they show tremendous promise. Field testing on our system demonstrated remarkable results: a traditional crew of four workers averages 100-120 panels per 10-hour shift, while a two-person crew working with robots installed 350 panels in an 8-hour shift, increasing productivity while simultaneously reducing injury risk.

The impact on worker physical strain is equally significant. A manual crew installing 600 panels walks approximately 4.5 miles daily, carrying heavy materials for half that distance. Workers using robotic assistance might walk just half a mile daily without carrying panels, focusing instead on technical work that requires their expertise.

Whether it’s robotics or some other form of automation, the industry must embrace solutions that provide safer, faster and more cost-effective means of completing work, especially in challenging environments.

Leadership visibility: the human element of safety

While technology provides valuable tools, superintendent presence on jobsites creates the foundation for a safety culture.

Workers develop more trust in their leadership when they’re in the field. In addition to building rapport between superintendents and their crews, visibility serves multiple purposes. Leaders can observe real-time behaviors and immediately coach for improved practices; they provide fresh eyes that spot unsafe conditions missed in formal inspections and, most importantly, their presence encourages open communication.

Ask just about any worker, and they’ll admit they feel more comfortable speaking up when they believe leadership cares. This creates opportunities for informal conversations where hidden concerns or improvement ideas surface. The results are measurable: lower incident rates, fewer violations, quicker corrections and improved participation in safety processes.

Worker empowerment programs

Forward-thinking contractors are implementing structured systems that enable field workers to report safety concerns and improvement suggestions. These programs follow a simple process: workers identify issues, report them through accessible channels and management responds promptly. This approach transforms safety from a top-down directive to a collaborative effort.

For instance, Rosendin’s Craft Empowerment Program provides a safe space for workers to share their thoughts and experiences. If they see something unsafe or has the potential to be a problem, they’re encouraged to come forward. CEP leaders wear a different-colored safety vest to be visible on the job at all times. Their job is to ensure comments and complaints are addressed.

When employees share their concerns, leaders act, validate and value their input. So we hold weekly meetings with supervisors to review all CEP issues and take steps if necessary to make changes.

The key to success is following up. Workers need to know the outcome of their contributions — whether the hazard was corrected or why a suggestion couldn’t be implemented. This respect builds ownership and reinforces that workers are integral to solutions.

Upgrading basic protection

Even basic safety equipment deserves innovative thinking, like using multi-color safety vests on jobsites, providing harnesses for smaller frames and transitioning from hard hats to safety helmets. After extensive evaluation, many contractors have decided to switch to safety helmets with chinstraps.

The primary reasons are design and fit impact protection and stability. Hard hats are designed with a suspension system inside the shell, which fits loosely and can easily fall off if not ratcheted to an uncomfortable tightness. Safety helmets modeled after climbing and biking gear have a more secure fit, internal padding and an adjustable 4-point chinstrap.

Traditional hard hats primarily protect against top-down impacts, which can easily come off during falls, when working in awkward positions or even in a stiff wind. However, safety helmets remain secure on the head, even in a fall or collision, and are rated for multi-directional protection (top, sides, front and back). They are also often tested to higher standards (e.g., ANSI Z89.1 Type II or EN 12492).

Both types of head protection can accommodate visors, earmuffs, lights and shade cloths. However, safety helmets can also be fitted with cooling pads and are more comfortable for extended periods. While traditional hard hats remain common on construction sites, safety helmets are rapidly becoming the industry standard.

The most effective safety programs balance technological innovation with human-centered practices. Automation can reduce physical strain while improving productivity, and new approaches to safety helmets can encourage users to swap out older gear. But ultimately, leadership visibility and worker empowerment programs are needed on every jobsite to create the communication channels and trust necessary for continuous improvement.

The lesson for construction superintendents is clear: invest in innovative tools and relationship-building practices. Technology can reduce physical risks, but only engaged workers who feel valued will fully embrace and enhance a safety culture.

Kyle Kirkpatrick, CSP, SMP, is Rosendin’s corporate director of safety – Renewables.

Join our thriving community of 70,000+ superintendents and trade professionals on LinkedIn!

Join our thriving community of 70,000+ superintendents and trade professionals on LinkedIn! Search our job board for your next opportunity, or post an opening within your company.

Search our job board for your next opportunity, or post an opening within your company. Subscribe to our monthly

Construction Superintendent eNewsletter and stay current.

Subscribe to our monthly

Construction Superintendent eNewsletter and stay current.