Cutting-edge technology + old world skills meet in the middle

By Robbie Lund

As a superintendent, I’ve developed a dual expertise in historic renovations and construction technology. Familiar with the ins and outs of a jobsite, I also complete my own 3D modeling. In addition, I serve as an advisory superintendent for multiple projects, particularly in the preconstruction and planning phases. Recently, I had the opportunity to work on two historical renovations—the University of Washington’s Denny Hall, and the Seattle Asian Art Museum. The following includes takeaways from both projects, which can then be applied to future historic renovations to help preserve our heritage.

Denny Hall

The Denny Hall project is a $36-million, 90,000-square-foot historic renovation on the University of Washington’s Seattle campus. Denny Hall was built in 1894, and is now listed in the Washington State Heritage Register, one of the oldest structures in Seattle. It has four floors, a two-story attic, plus an additional two-story-tall bell tower. To this day, the bell tower houses the bell from the original 1860’s campus. The renovation included upgrading all major building systems, correcting seismic deficiencies, new thermal envelope updates, all new interior finishes, a new elevator and a new four-story open-air stair in the heart of the structure.

Primary lessons learned from this project included:

- Be patient

- Build a team

- Trust your partners

- Accommodate special requests

1) Be patient

Preconstruction for historical renovations can take years. Permitting is difficult because these buildings are often on historical registries, which requires working with multiple agencies. There can be regional, state and national Landmarks Boards, all of which require a meticulous surveying package. Focused on preserving for future generations, they decide what must be saved and what can be demolished.

Denny Hall was unique because UW retained all rights to the building, with its own internal Landmarks Board. It took the board over a year to decide what elements to save. BNBuilders won the project in 2008 but, due to the recession, wasn’t able to start until 2014. After an additional eight months of preconstruction, construction officially started in June 2015, and completed six months early in June 2016. The planning, permitting and preconstruction required much more patience than a typical renovation.

2) Build a team

With Denny Hall, team building was essential. Because it was such a complicated project, it was critical that everyone understood the plan and worked together. There were daily huddles with all trade partners onsite where visual schedules and models (aided by laser scanning) helped communicate the vision. All of the trade partners were able to understand our unconventional methods because they understood the big picture. It was hugely satisfying when almost every contractor said it was their favorite job upon completion.

3) Trust your partners

There were 41 trade partners on the Denny Hall project. We informed partners of the general plan, but asked for their input and left room for their creativity. The work was completed better and faster this way. For example, the demolition contractor suggested opening up walls to be more efficient with his equipment, and to use the old mechanical shafts as demo chutes. It shaved weeks off the schedule and prevented double handling the same material. Also, the framing contractor suggested a custom metal fabricator, so that each window didn’t have to be custom framed. The contractor also suggested first framing on the wings of the building while other crews worked in the more complicated center, which was a huge time saver. Finally, the structural engineer had the difficult task of assisting us with figuring out how to install a large shoring tower to hold up the roof, bell tower and a large concrete “bathtub” mechanical room in the attic. This had to be in place prior to removing the core of the building to make room for a new atrium.

4) Accommodate special requests

Historical renovations often come with a unique set of needs. The original bell in Denny Hall’s bell tower stays silent except for one annual event—homecoming. In 2015, homecoming fell in the middle of demolition. Because this was an important tradition, construction crews erected a scaffolding and rigged a rope so the homecoming bell could ring even in the midst of construction.

Demolition crews also found the original cornerstone of Denny Hall, hiding just below the grade behind overgrown foliage. The landscaping design was adjusted so the original cornerstone, with the chiseled university seal, could be exposed.

Seattle Asian Art Museum

The Seattle Asian Art Museum’s historic Art Deco building was constructed in the 1930s during the Great Depression. The museum was designed by Carl F. Gould, a Paris-trained Seattle architect, and is located in the Olmsted-designed Volunteer Park. This project includes a renovation and a 7,000-square-foot addition. Approval from the Landmarks Boards came between May 2016 and September 2017. Preconstruction was a one-and-a-half-year process, and construction began February 2018. Estimated completion is June 2019.

Lessons learned include:

- Control your climate

- Rely on cutting-edge technology and old world skills

5) Control your climate

Unlike most typical construction, historical elements may require a strict climate. The SAAM project, filled with precious artwork, stained glass, historical tile and antique plaster, requires a narrow temperature window, which must be maintained at all times.

6) Rely on cutting-edge technology and Old World skills

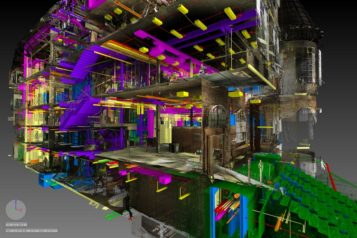

Historical renovations often require a combination of the latest technology and time-honored craftsmanship to keep historical elements intact. For SAAM, crews used technological tools to minimize surprises. In addition to time spent onsite, every inch was laser scanned. Holes were cut into walls slated to be demolished to render the findings into 3D models, and composite 3D images, put together with architectural models.

Even with today’s technology, the historical elements may require outside expertise. In the SAAM project, walls were created using scagliola (pronounced scal-yo-lah), a plaster technique no longer used today that mimics the look and feel of natural stone. Construction crews found a rare expert to advise on how to preserve and work around the plaster.

Historical renovations bring a unique set of challenges, but also a unique set of rewards. Often, while working to preserve the best of yesteryear’s creativity in the built environment, we honor that spirit of creativity with our own ingenuity and innovation.

Robbie Lund is a superintendent with BNBuilders. For more information about BNBuilders, visit www.bnbuilders.com.

Join our thriving community of 70,000+ superintendents and trade professionals on LinkedIn!

Join our thriving community of 70,000+ superintendents and trade professionals on LinkedIn! Search our job board for your next opportunity, or post an opening within your company.

Search our job board for your next opportunity, or post an opening within your company. Subscribe to our monthly

Construction Superintendent eNewsletter and stay current.

Subscribe to our monthly

Construction Superintendent eNewsletter and stay current.