Best practices to recognize warning signs, keep crews safe

By Nicole Moyen

Not only are average temperatures increasing globally, but the number of extreme hot days are also on the uptick. This year is projected to be one of the hottest on record, so it’s important to take precautions to keep your crews safe in the heat.

Despite the fact that NIOSH and OSHA have created guidelines for heat safety, they are not followed at many jobsites as they are not mandatory standards. Heat-related medical care and productivity losses cost the U.S. up to $6.2 billion, and are estimated to reach $2 trillion by 2030. Productivity losses account for a large part of this economic burden, as 30% of workers experience lower productivity when working in the heat. In addition, heat-related deaths increase by approximately 37% with each 1 F rise in temperatures in the atmosphere.

These statistics are troubling, because heat-related injuries and illnesses are 100% preventable if fairly inexpensive practices are taken. Below are ways to keep your crews free from heat injuries and illnesses and stay productive, even on the hottest days.

Heat exhaustion vs. exertional heat stroke

Heat illnesses include heat exhaustion and exertional heat stroke. The biggest misconception is that workers will experience heat exhaustion before showing signs and symptoms of exertional heat stroke. This is not true. In fact, someone might not show any indication they need to take a break until their core body temperature has reached a point where they are exhibiting signs and symptoms of exertional heat stroke, and often, it can come about very suddenly without much warning.

If you don’t have a way to get an accurate core body temperature to diagnose exertional heat stroke, the best indicators you need to immediately cool someone (e.g., put them in an ice water bath immersion) include:

- Weakness or inability to work, especially collapsing or fainting.

- Personality and behavior changes. This is one of the main differentiators in symptoms between heat exhaustion and exertional heat stroke. Workers experiencing exertional heat stroke might hallucinate, become aggressive, confused or irritable. If your worker is exhibiting uncharacteristic behaviors, cool them immediately and call 911.

Exertional heat stroke is a medical emergency. When in doubt, cool the worker and call 911. Better to err on the side of caution, as death from exertional heat stroke is avoidable if the person is cooled within 30 minutes of first experiencing symptoms.

Heat exhaustion, on the other hand, is not a medical emergency, and workers typically recover within 15 minutes if given proper rest and fluids. If your workers start to feel lightheaded, fatigued, faint, have goosebumps or chills and are hot and sweaty, they are likely experiencing heat exhaustion. Vomiting can also be a sign of heat exhaustion.

Workers should rest immediately upon experiencing these signs and symptoms. Find shade or an air-cooled trailer on the jobsite, drink plenty of fluids and remove extra clothing layers to help cool faster. If the worker is feeling lightheaded or faint, they can lay down and prop their feet up on a chair to help return blood to the brain. Ice cold towels can also be used to help workers cool off.

Avoiding exertional heat stroke on the jobsite

Provide frequent rest. On hot days, make sure workers are taking frequent breaks in a cooler location, such as inside an air-cooled trailer on the jobsite or in a properly shaded area.

Listen to workers. Although work/rest schedules might provide a general guideline for your workers, they will not work for everyone, as many factors (e.g., medications, fitness, age) can affect a person’s ability to properly regulate their temperature. The best thing you can do is to check in with your workers to see how they are feeling. Try to understand and establish baseline behaviors and work rates for each individual so you can identify when someone is acting outside of the norm. Talk with your workers throughout the day or establish a buddy system so they have someone checking in with them to make sure that, if they exhibit unusual behavior or don’t feel well, they are immediately removed from the heat and cooled. Make it acceptable for workers to take a break outside of a designated rest period if they’re not feeling well—especially on hot days.

Improve workers’ ability to cool off. Try to create an environment for workers to stay cool. The main way the body cools is by sweating. But our sweat must be wicked away for it to actually cool us down; dripping sweat doesn’t cool you down and actually leads to dehydration. You can provide towels to workers so they can towel their skin dry as much as possible to allow sweat to continue to evaporate. Sweat sitting or pooling on the skin can decrease sweat rate, which will lead to a faster increase in core temperature. If possible, place an electric fan near your workers to aid in cooling their bodies by helping sweat to evaporate via air motion.

Encourage hydration. Proper hydration is imperative for workers, especially on hot days where sweat rates are high. When it’s hot outside, sweat rates will be higher, meaning workers will be losing a lot more body water and therefore be at greater risk for dehydration. Dehydration exacerbates the effects of heat stress on the body, leading to a decreased sweat rate and faster increase in core body temperature. Dehydration also leads to reduction in mood and cognition.

Provide workers with potable water in both rest and working areas. In situations where they don’t have access to a water station, encourage workers to carry water with them. Even if it can’t be kept cold, warm water still hydrates and does not increase body temperature. Never limit a worker’s water intake and make sure they can always drink when they’re thirsty.

NIOSH and OSHA recommend drinking approximately 8 ounces of water (1 cup) every 15-20 minutes throughout the workday. But that amount may not be correct for every person. For a more accurate hydration plan, you can calculate your worker’s normal sweat rate to arrive at the proper recommendation for water intake. In the meantime, the rule of thumb is to drink approximately 20 ounces (about 1.5 standard water bottles) of water per pound of body weight lost through sweating. Workers can weigh themselves nude before and after work to calculate how much water they’ve lost during the workday, and aim to rehydrate at night before arriving at work the next day.

Importantly, encourage your workers to drink plenty of fluids before even arriving at work. Drink a large glass of water first thing in the morning, even before ingesting caffeine. Workers can check their urine color to ensure they are hydrated—it should be a clear to light lemonade color. Starting the day well hydrated will keep their core body temperature lower throughout the workday, and help to maintain mood, cognition and productivity.

Returning to work post-illness

With the continued incidence of COVID-19 infections across the U.S., it’s likely that many workers may miss work due to infection. When they return to the jobsite, they will likely have lost their heat acclimatization, as it starts to diminish after approximately five days. Since workers are most susceptible to heat-related injuries and illnesses during the first few days back on the job (when they’re not yet heat acclimatized), it is important to keep an eye on workers for signs and symptoms of heat injury or illnesses and encourage them to rest if needed. Allow any workers who have been off the job for more than five days to ease back into work by giving them lighter workloads and reduce heavy clothing, if possible, for a few days until they are heat acclimatized. Workers can wear the full PPE uniform after six days of working in the heat. Allowing your workers to ease into work after an absence will pay off in the long run, as you’ll have less heat injuries and illnesses.

Introduce smart PPE

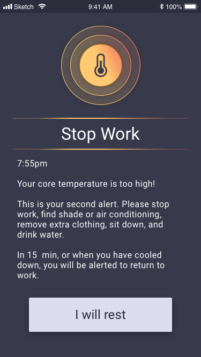

Technology exists that monitors workers’ body temperature and heart rate to prevent heat-related injuries and illnesses. Smart PPE can provide real-time data on how each worker is faring in hot conditions. Such PPE alerts both the worker and the superintendent when a physiological indicator is reached or has exceeded ideal levels and prompts an intervention—such as stopping work, resting or alerting medics if the situation is serious.

Technology exists that monitors workers’ body temperature and heart rate to prevent heat-related injuries and illnesses. Smart PPE can provide real-time data on how each worker is faring in hot conditions. Such PPE alerts both the worker and the superintendent when a physiological indicator is reached or has exceeded ideal levels and prompts an intervention—such as stopping work, resting or alerting medics if the situation is serious.

Individualized data allows for greater levels of safeguarding the crew, accommodating for the individual’s’ particular health situation, such as their fitness level, nutrition, current disease state, gender and other factors.

Importantly, make sure the smart PPE you’re using is intrinsically safe to protect your workers. This is a certification that companies can obtain that indicates their device or technology will not explode in hazardous working environments, such as in the oil and gas industry.

Keep a step ahead

Check the weather (black globe, temperature and humidity) throughout the day—at least every two hours—and update work/rest schedules accordingly if the criteria change. For example, the risk of heat injuries and illnesses can change not only with temperature, but especially with relative humidity and radiative heat loads (i.e., black globe temperature).

Finally, ensure your jobsite is set up for success by providing rest and water stations, an emergency ice water bath onsite and a way to monitor the weather. Managing the safety of workers in heat will become an even greater priority as climate change increases temperature extremes. But the good news is heat-related injuries and illnesses are 100% preventable if the right actions are taken.

Nicole Moyen leads R&D at Kenzen.

References

Kenny, Glen P., et al. “Climate Change and Heat Exposure: Impact on Health in Occupational and General Populations.” Exertional Heat Illness. Springer, Cham, 2020. 225-261.

Quick Questions in Heat-Related Illness and Hydration: Expert Advice in Sports Medicine. National Athletic Trainers’ Association & SLACK Inc., 2015. Editor: Rebecca M. Lopez.

Join our thriving community of 70,000+ superintendents and trade professionals on LinkedIn!

Join our thriving community of 70,000+ superintendents and trade professionals on LinkedIn! Search our job board for your next opportunity, or post an opening within your company.

Search our job board for your next opportunity, or post an opening within your company. Subscribe to our monthly

Construction Superintendent eNewsletter and stay current.

Subscribe to our monthly

Construction Superintendent eNewsletter and stay current.