By Tyler Williams

The labor shortage in the construction trades is being felt by every contractor nationwide while, at the same time, speed-to-market pressures from customers are as strong as ever. We’re working to build the next generation of workers in the skilled trades, but we need to build today’s jobs at the same time.

So, there’s a conundrum: crews in the field have little appetite for disruption, but new methods of working that could make delivery more efficient need time to take hold. We are surrounded by potential “solutions” to construction problems, but how do you know what is going to work, without adding noise and distractions around field crews? Even a superintendent that wants to try out a new tool or method is going to hesitate when the price of something not going right may be very high.

So how do we advance more efficient means of working while respecting the schedules – and skepticism – of the crews we lead? It begins with making sure construction firm innovation groups include people with robust field experience who can speak the language of the trades and are willing to listen.

Too often in our industry, innovation seems to be disconnected from the work we do in the field. One way to break that pattern is for firms to let people in the field drive their portion of the discussion. One thing we tried at DPR Construction was prompting crews to submit “opportunities for innovation.” For starters, most members of our craft team, including more than 3,500 self-performing workers, don’t have access to traditional intranet tools (and even if they did, it’s not convenient in the field).

We piloted an OFI program in Seattle, Washington and received several ideas for improving work processes directly from crews using a simple QR code and submission page. A similar effort in Sacramento, California though, yielded little feedback. Why? In Seattle, we made sure the effort was led by superintendents and foremen that were actively involved in the program and the field. In Sacramento, we tried to utilize signage, a breakfast promotion and a team member who was excited about the idea but did not have the field experience that our Seattle pilot did. Having a dedicated champion for innovation in the field matters. In other areas where we’ve deployed the OFI program, we see more ideas coming from crews when a superintendent actively leads the effort.

Of course, another key is following up… and doing so in a way that connects with the field. A whiz-bang tech solution seems to be industry default, but you don’t need digital screens to make a difference.

For example, on a Seattle-area healthcare project, a crew reached out wondering if there was a better solution for drywallers when it came to dust collection. The normal process of drywall work creates a lot of dust, a hazard and an inconvenience, and cleaning it up adds time. We were able to contact one of our tool manufacturer partners who let us pilot a new prototype device that attaches to a router, letting drywallers keep two hands on the router while the device vacuums up the dust simultaneously. It’s a perfect solution, but how it came to be is what really makes it work: a crew gave feedback to a superintendent who had the network to find a tool that aligned with workflows.

That network is key, however. It is vital for firms to make sure they’re not just coming up with ideas, but are also building relationships with the craft to make sure the ideas they’re incubating connect with them. To get there, DPR has a dedicated field innovation leader that has the knowledge and experience of the field (I’m a former superintendent & union carpenter, for instance) who can connect what’s happening in both the office and field environments to deliver solutions to actual field challenges.

In addition, as the FIL, I have built strategic connections with several natural field innovators across DPR’s offices and they work to identify opportunities where field innovations can make an impact to our frontline workers. We’re able to communicate with the field in the ways we always have as superintendents, just more focused on how we can support them through new methods.

Our strategy of empowering people with decades of experience in the field to look at what they do and suggest new things is gaining traction. For a longtime doors/frames/hardware team, members suggested a system of QR codes linked to live versions of drawings. All workers need are their phones and they have up-to-date information on how to proceed at a specific location.

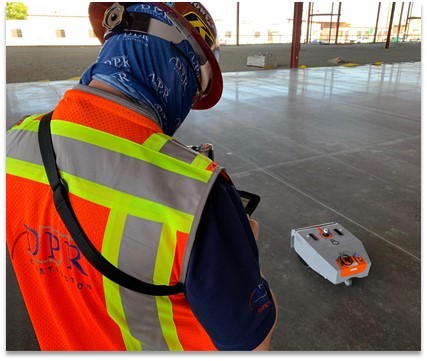

One team in Spokane, Washington wanted to test a new exo-suit from Hilti for certain kinds of work and are providing feedback to the vendor in return. In the face of the pandemic, teams suggested ways to orchestrate remote site visits for EHS and inspection purposes, but without the bulkiness of a headset. Instead, the solution works with traditional safety glasses and a smartphone.

The common thread? All of these ideas were born in the field, shared with a craft innovation champion (often face-to-face) and then addressed with a tool that can be integrated into normal workflows, not a wholesale change. By only addressing what’s not as efficient within a process, rather than deeming the entire process to be bad, we’re becoming more effective in ways that we believe are sustainable. In addition, if we utilize the frontline workers to strategically identify common field problems, we are empowering our workforce to assist with the potential solutions. That reduces perceptions that innovation can add noise and distractions to our project teams.

Superintendents and their crews have a lot to offer innovation teams throughout our industry, but it takes making sure those voices are heard and understood to make real change happen. By leveraging field leadership to inspire innovations “for the field” and not “to the field,” new idea bridges can be built and communicated to company leadership so we can leverage all our relationships to meet the challenges of our projects.

Tyler Williams, a former DPR Construction superintendent, is a field innovation leader for the firm.

Join our thriving community of 70,000+ superintendents and trade professionals on LinkedIn!

Join our thriving community of 70,000+ superintendents and trade professionals on LinkedIn! Search our job board for your next opportunity, or post an opening within your company.

Search our job board for your next opportunity, or post an opening within your company. Subscribe to our monthly

Construction Superintendent eNewsletter and stay current.

Subscribe to our monthly

Construction Superintendent eNewsletter and stay current.